Romanian Peasant Art

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:103:]]Romanian Peasant Art

By Octavian Buhociu

The characteristic feature of Romanian folk arts is the recurrence of a specifically abstract style of designing in the decoration of the peasants, houses, in their costumes, their carpets and embroideries, in the craftsmanship displayed in the ornamentation of the simplest implements and household objects, in the enamelling and in the ingeniously multicoloured staining of Easter eggs. Take, for example, the beautiful carpets, mats and tapestries woven by Romanian housewives to drape the benches and walls of their simple little houses built of straw and earth. Colouring varies from region to region, ranging from the bright reds and yellows of Oltenian tapestries to the darker hues of old Bessarabian carpets; yet they all display the same perfect harmony of design, the same simple figure-drawing and the same abstract style of artistic expression. Romanian folkart transcends the mere imitation of nature; it reflects profound inner feelings, an intense spiritual life and an age-long tradition. On the background of a Roumanian carpet, the subjects borrowed from nature - field flowers, tree-leaves or birds acquire a strangely artless yet cunning gracefulness. The peasant craftsman seems inspired with a curious geometrical spirit, though there is nothing in the conventions of his art which resembles the mechanical uniformity of industrial mass production.

Each tapestry has an individuality of its own - a simply but genuinely poetic expression of nature. The leaves of plants may look like wings and birds like flowers. Flowers may resemble butterflies and weirdly twisted branches seem like a mysterious primitive writing - the secret hieroglyphics of a nation's inmost thoughts. The same pleasing fancies are seen in the national costume. Every garment is embroidered. The peasant's rough linen shirt is embroidered with coloured wools or with gold or silver thread, while the white skin of the cojoc - a cloak worn in winter-time by the men and by the women and made of sheepskins with the wooly fleece turned inside as a lining is also ornately embroidered with multicoloured wools. But the most ornamental and richly embroidered article of wearing apparel is the women's fota, consisting either of two aprons reaching from the waist to just above the ankle or of a single piece forming skirt. In some parts of the country - in the Banat, for example, the fota consists of long fringes of red threads which give an elegant and even sumptuous appearance to the whole costume. A characteristic feature of the women's dress cannot fail to attract attention. This is the veil with which Romanian peasant women cover their heads. It is worn only by married women, the unmarried girls usually going bare-headed. The shape and material of the veil vary from region to regions. Made of fine, thin flax or white silk, the veil covers the whole of the head except the face and sometimes falls in fluttering folds over the shoulders and back, reaching down to the waist in some districts. Imagination, inventiveness and a talent for combining patterns and colours have found full scope in the graceful simplicity of the women's veil.

Formerly, the peasant's costume was ornamented with woolen threads woven with distaff and spindle. Later, cotton began to take the place of the patriarchal wool. The colouring varies with the region, and a connoisseur can tell at a glance the district in which a shirt or a blouse was or a skirt made. The patterns are characteristic all over the whole country. Long stripes of red or golden thread cover the front of the shirt. Sometimes the shirt is adorned with tiny discs of thin yellow metal or with small pearls. Every article of woven material - shirts, skirts, petticoats, veils, towels, curtains - is embroidered and ornamented with delicate needlework.

The most striking feature of Roumanian embroideries and needlework in general is an idealization of the shapes which Nature has to offer and an avoidance of life-like reproductions. This striving after interpretation is unpremedidated and must be ascribed to an instinctive artistic urge of the Romanian people. All other forms of Romanian folk art show the same candour. The patterns embroidered on shirts in coloured threads consist of geometrical figures cutting into, yet harmonizing with, one another, and of idealized and angular flowers, leaves and twigs.

There is everywhere an avoidance of the curved line. A strict realism is sacrificed in favour of artistic interpretation. These articles of clothing are embroidered in the same style of design as the carpets and tapestries. The dominant note is struck by the geometrical line and an abstract reproduction of the forms of every kind of element in the vegetable and animal kingdoms. The geometrical regularity of rhomboids, zigzags, crosses and circles interseting one another in minutely complicated patterns is unexpectedly broken by picturesquely allusive shapes of flowers, leaves and birds. There is always an embroidered hem or a gracefully twisted thread to give even the poorest costume an air of gaiety and decoration.

This deep-rooted love of embellishment is also strongly expressed in the Romanian peasant's wood sculptures and carvings and in various wooden ornaments with which his house is adorned. The first object to catch the eye as one enters a peasant's house is the massive and friendly gateway to the courtyard. Three strong posts divide it in two unequal parts, the larger one for the passage of carts and the smaller one to form a narrow doorway. The posts support the wide eaves of a little roof of thin strips of wood, giving a monumental appearance to the gateway. Both the posts and the doors are richly sculptured, the ornamental carvings on the doors producing the effect of wooden lace. Similar carvings adorn the posts of the balcony of the house.

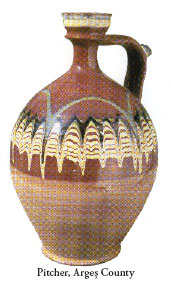

The balcony gives the peasant's house an appearance of gay and open hospitality. It generally leads into the hall of the house, a long room dividing the house into two parts. The centre of the household life is a broad and massive hearth which takes up the whole width of the room. A wooden bench, as broad as a bed and piled up with embroidered cushions, coverlets and blankets, runs round the walls of the room. Thick beams in the ceiling give the room a solid appearance. Hanging in the place of honour in a corner facing eastwards or between the windows, ancient wooden icons, naively yet expressively coloured are lit up by the flickering flame of an ever-burning candle. The next most valued ornaments after the icons and the carpets are the enameled pitchers, bowls and dishes set in a row along the top of the walls. The more prosperous the household, the more numerous are the bedspreads, coverlets and embroideries covering the walls, benches, beds and tables and hanging from the windows or which fill the heavy and capacious chests that serve as cupboards for all valuable objects. Wealth and status are best indicated by an abundance of embroideries, carpets and ornamented bowls. The household furniture, on the other hand, is always simple and strictly utilitarian. Apart from small regional differences, every house has the same table, usually circular in shape with three-legged chairs around it, the same bench along the walls and the same cooking utensils and icons. It is the embroideries which cover and adorn everything in the peasant's house which give it its specific character. Wood sculpturing and carving is, perhaps, the most widespread of the Romanian peasant's arts, for wood is his most common and often his only material. His artistry attains an astonishing perfection. He exercises his inexhaustible and sometimes unexpected fancy on every kind of object, from the troita - a wooden votive monument - or the door fo the house or a shepherd's staff, notched and dappled with inscriptions and patterns, to agricultural implements and household utensils of all varieties - the handles of wooden spoons and jugs, pitchforks, oars, whips and measuring pots. By ding of long hours of patient and meticulous work, the peasant artist can skillfully design with a simple pocketknife the most fantastic and complicated figures.

Yet the most interesting expression of Romanian folkart is, perhaps, the troita or "trinity". The troita has evolved from a simple wooden cross placed at crossroad in memory of an old occurrence or erected as a token of pious gratitude into a wooden monument more like a small shrine. It consists of a cross of four, six or eight pairs of arms supported by a thick pedestal and covered by a small roof of thin strips of wood. Delicate carvings adorn the troita which sometimes carries a number of ikons on its arms and seems like a strange curtain in the open air. The troita is, perhaps, the most authentic form of native Romanian religious architecture and represents the indigenous art of wood sculpture in its finest form. The Romanian peasant artist's longing urge to harmonise colours is revealed in his pottery. Next to the walls hung with ikons, the most striking parts of the peasant's house are the walls kept for the household pots and pans. Here, rows of daintly coloured bowls, pots, jugs, ewers and pitchers of all shapes stand along shelves bordered with a wooden trellis. Some of the bowls are lightly marked with fine curling lines of colours, thin blades of grass on a white or grey background. The rounded bellies of ewers and the necks of jugs are streaked with splashes of colour representing petals and leaves. The colouring is in clear, light and softly delicate tones which do not weary the eye. They are the colours of modest field flowers - the fresh and tender blue of the cyclamen, the yellow of the cowslip, the dark green of the prickles of the fir-tree, the deep purple of the ripe plum, the delicate mauve of the marshmallow, the golden heart of the chamomile, the limpid violet of the sage-flower. Even when the pattern is more complicated, when the lines are intertwined in lacelike knots and when the colouring is more diverse, the effect is not one of heaviness and overloading but of circumspect abundance. The white spaces of the background are purposely let clear so that the decorative coluring may stand out without fatiguing the eye or straining the attention, for the peasant enameller never loses himself in details or overlooks the harmony of the hwole.

Yet the most interesting expression of Romanian folkart is, perhaps, the troita or "trinity". The troita has evolved from a simple wooden cross placed at crossroad in memory of an old occurrence or erected as a token of pious gratitude into a wooden monument more like a small shrine. It consists of a cross of four, six or eight pairs of arms supported by a thick pedestal and covered by a small roof of thin strips of wood. Delicate carvings adorn the troita which sometimes carries a number of ikons on its arms and seems like a strange curtain in the open air. The troita is, perhaps, the most authentic form of native Romanian religious architecture and represents the indigenous art of wood sculpture in its finest form. The Romanian peasant artist's longing urge to harmonise colours is revealed in his pottery. Next to the walls hung with ikons, the most striking parts of the peasant's house are the walls kept for the household pots and pans. Here, rows of daintly coloured bowls, pots, jugs, ewers and pitchers of all shapes stand along shelves bordered with a wooden trellis. Some of the bowls are lightly marked with fine curling lines of colours, thin blades of grass on a white or grey background. The rounded bellies of ewers and the necks of jugs are streaked with splashes of colour representing petals and leaves. The colouring is in clear, light and softly delicate tones which do not weary the eye. They are the colours of modest field flowers - the fresh and tender blue of the cyclamen, the yellow of the cowslip, the dark green of the prickles of the fir-tree, the deep purple of the ripe plum, the delicate mauve of the marshmallow, the golden heart of the chamomile, the limpid violet of the sage-flower. Even when the pattern is more complicated, when the lines are intertwined in lacelike knots and when the colouring is more diverse, the effect is not one of heaviness and overloading but of circumspect abundance. The white spaces of the background are purposely let clear so that the decorative coluring may stand out without fatiguing the eye or straining the attention, for the peasant enameller never loses himself in details or overlooks the harmony of the hwole.

Another interesting Roumanian folk art is the old custom of staining Easter eggs.

On the tiny surface of an eggshell, scope is found for an infinitely varied arrangements of lines and colours. Although the womenfolk of the peasantry stain their Easter eggs - "red eggs", as they are generically called - in all kinds of colours, they can reproduce in an abstract manner every species of animal and plant, every shaped form of nature and life. The stained eggs are called by a multitude of quaintly poetic names after the subject which they represent, ranging from "frog's eye" or "frog's leg" to "starry way", from "wrathful woman" to "bishop's croisier" and from "shepherd's bag" to "friar's eudgel".

Proportion, Economy of line, harmony and balance are the keynotes of Roumanian folk arts.

Wisdom and profound originality are expressed in their primitive yet powerful forms. Springing from the collective conscience of an unusually homogenous people, and despite, or perhaps, because of so many storms of history, the art of Roumania has sought and found in a striving after beauty a consolation, an invigoration of love of life and a splendid affirmation of its own genius.

Comentarii